Despite high levels of economic growth and improvements on poverty and education, progress on child labour has stalled in the manufacturing countries most entwined with global apparel supply chains, new research has shown.

Key manufacturing hubs – including China, India, Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia – have registered no tangible improvement in a ranking of 198 countries since 2016.

The latest annual ‘Child Labour Index’ from global risk analytics company Verisk Maplecroft identifies 27 countries – which account for roughly 12% of the world’s total population, or 900m people – where child labour poses an ‘extreme risk.’

The index, which has been developed to enable companies to identify where the risk of association or complicity with child labour is highest in their supply chains, measures the frequency and severity of violations, a country’s adoption of laws and international treaties, and its ability and will to enforce them.

With five of the ten highest risk countries, East Africa is the highest risk region.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataSee Also:

The 10 worst performing countries in 2019 are: North Korea (ranked 1st and highest risk globally), Somalia (2), South Sudan (3), Eritrea (4), Central African Republic (5), Sudan (6), Venezuela (7), Papua New Guinea (8), Chad (9) and Mozambique (10).

Manufacturing supply chains

A further 82 countries are categorised as ‘high risk’ in the index, including Asia’s economic giants India (ranked 47th) and China (98). The research shows that despite meteoric economic growth, there has been little or no improvement in their index scores in recent years.

Worryingly for organisations with extended supply chains, this trend is echoed across many manufacturing countries, including Ethiopia (30), Bangladesh (44), Turkey (63) and Vietnam (81), where the high risk of children being exploited or having to work through necessity remains unchanged.

“The economic momentum of many countries is yet to trickle down to the poorest in society and any meaningful headway on labour rights issues, including child labour, remains elusive,” says Oscar Larsson, human rights data analyst at Verisk Maplecroft.

“Child labour is still prevalent across many sectors – if countries aren’t taking action it is up to companies to see they have the tools to make sure it’s not happening under their watch.”

Red flags in China and India include apparel

While China and India are categorised as ‘high risk’ overall, it’s important to note that they are scored as ‘extreme risk’ in the section of the Child Labour Index measuring the frequency and severity of violations.

Both have signed up to all relevant international treaties, which improves their position in the ranking – but unlike China, India’s domestic laws fall short of ILO standards on the legal working age of 15, and its enforcement capabilities lack significant resources and coverage. These factors ensure that South Asia’s largest economy is among the 25% worst performing countries globally.

According to Verisk Maplecroft’s Industry Risk Data, agriculture, manufacturing, apparel, construction, mining and hospitality all pose high levels of risk in both countries. Trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation of children are also severe issues.

Child labour highs and lows

The country seeing the highest increase in child labour risks is Venezuela. Continuing political and social instability has seen it fall 80 places in the index since 2016 and it now ranks 7th highest risk globally. Other notable countries seeing an increase in risk include Nigeria and Cambodia, both of which have dropped into the ‘extreme risk’ category.

On the flipside, 57 countries have registered significant improvements in the index between 2017 and 2019 and feature sourcing locations tied to global apparel supply chains. Myanmar improved from 3rd highest risk globally in 2018 to 27th this year; while Madagascar has climbed 20 places to 45th since 2017.

The index shows the countries have increased their enforcement capabilities and commitments towards fighting child labour, but Myanmar has also experienced fewer reported violations.

• While many apparel companies have made significant progress towards eliminating child labour in the factories where their clothes are made, some of the most extreme risks lie further down the supply chain in the farms where the raw materials used by the industry are produced.

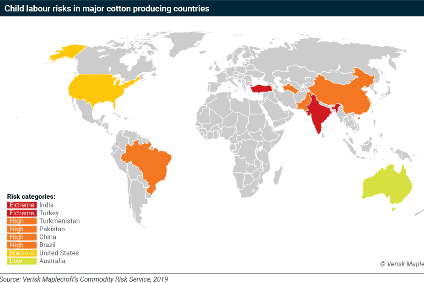

• Agriculture is one of the highest risk sectors for child labour and constitutes a significant challenge for the sustainable procurement departments of multinationals. Out of the eight countries Verisk Maplecroft scores for child labour risks in cotton production, six are rated as ‘high’ or ‘extreme risk,’ including Turkey, Brazil, Pakistan and Turkmenistan.

• The trend for cotton and silk mirrors that of the overall child labour situation with major producers, including India (‘extreme risk’) and China (‘high risk’), showing little or no improvement in tackling the issue head on.

• According to Verisk Maplecroft’s Commodity Risk Service, India, which is the world’s leading producer of cotton and second-largest producer of silk, is considered extreme risk for potential association with child labour for the production of both commodities. Indeed, over 25% of the workforce involved in cotton production is under the age of 14 according to the India Committee of the Netherlands.

• One of the main drivers of child labour in cotton and silk production is a reliance on seasonal labour, where workers do not earn enough income and must rely on their children to participate in harvest, where they are often paid according to how much cotton or silk they collect.

• In Uzbekistan, silk farmers are given high production quotas by the government and must rely on family members, including children, to harvest enough silk. Public bodies, including schools, are also required to close during harvest and must meet production quotas, meaning that schoolchildren are often employed in harvesting. Farmers and organisations who do not meet their quotas are penalised.

• Other key materials used by the textile and apparel industry are considered high or extreme risk of links to child labour. These include cashmere from Mongolia and rubber produced in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. By comparison, the only natural material commonly used by the industry that did not have widespread links to child labour was wool.