Cost and time are the two big factors influencing off-shore versus domestic sourcing decisions. But other issues also come into play, such as ethics, sustainability, and patriotism. Here industry consultant Malcolm Newbery weighs up the arguments for and against, with a look at two companies in the US and UK who are surviving and prospering from re-shoring.

Re-shoring is the process of returning clothing manufacture from (predominately) low cost sourcing countries to domestic suppliers. In a recent just-style article – ‘Made in the USA’ apparel – Who’s selling what and for how much?’ – the following statements were made:

- That 46% of US fashion brands and apparel retailers said they sourced “Made in the USA” products. The fact is that 97% of US clothing consumption is imported.

- That by 2025 over 20% of consumption could come from “near-shore” sources (McKinsey and Business of Fashion: The State of Fashion 2019).

Of the top ten retailers selling “Made in the USA” apparel, according to EDITED in 2018, only one bought over 10% of its product lines from America. The weighted average was less than 1%. So, it is a very small niche and it is overwhelmingly womenswear. This is the clue to its potential. Womenswear trends are shorter lived and harder to predict, so quick response, shorter lead times and speedy replenishment might be a powerful commercial advantage.

A very brief history of off-shore sourcing

Where and when did domestic manufacturing all go wrong? The answer, for the US, UK and Western Europe is the 1980s. Driven by weak economics and fierce fashion retail competition, buyers sought the lowest prices.

See Also:

- The US, despite efforts to keep production domestic using the “quick response” by-line, started to move off-shore but locally (near-shoring).

- The UK followed its colonial history and went to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and China through Hong Kong.

- Western Europe went to North Africa (France and Italy), Eastern Europe and Turkey (Germany).

Sometimes this was done by investing in their own or closely controlled supplier’s factories. But this proved to be a risky strategy (sometimes referred to as the “baby bird”). If you have a baby bird, mummy and daddy bird have to constantly feed it worms. At one well-known UK retailer, we even called it “feeding the factories.” We had to give them a steady supply of purchase orders, even when we did not want to. So, in the 1990s, investments were quietly disposed of and retailers and brands turned to sourcing from low-cost independent manufacturers.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataThe final bursting of the barrier to low-cost sourcing was the end of the Multi-Fibre Agreement in 2005. When that happened, it ushered in a free-for-all. Every retail and branded buyer in the US and Europe jumped on a plane and went to China. China is now the largest exporter of apparel in the world by both value and volume.

Of course, there are still tariffs, and at the moment a nasty trade war between US and China. But the tariffs have not prevented an ever-growing percentage of clothing being imported from the Far East, the Indian sub-continent, Turkey and Central America.

The perceived cost disadvantage of domestic manufacturing

Fashion buyers are supposed to be rational business people. Sometimes, it does not feel like that. But if we look dispassionately at the numbers, we can evaluate the potential difference between a low-cost source (I have used China) and domestic (I have used UK but it would apply exactly the same to US or Western Europe).

We know low-cost is cheaper, but why is it cheaper and by how much? Table 1 shows a hypothetical but realistic garment costing.

We can review the major elements of the two costings and compare them:

- There is virtually no difference in materials cost;

- There is a huge difference in manufacturing cost because of the labour cost, even though the China overhead % is higher than domestic;

- Shipping is obviously much cheaper from domestic;

- The domestic supplier’s price is 67% more expensive than China;

- Because there is no tariff, the final domestic landed cost is 47% more.

These figures would change if the fabric were a larger or smaller percentage of the total (expensive or cheap fabric), but material costs in total for clothing typically lie between 35% and 50% of the finished asking price. We will assume for simplicity that the domestic landed cost is 50% more than the low cost source.

The perceived time (speed to market) advantage of domestic manufacturing

If domestic cannot win on the cost issue, what about its time advantage? The time issue was the original defence for US manufacturing, and it was lost, spectacularly. Why should it be different now? Because, proponents of re-shoring will say, the market is now much more concerned with:

- Short selling seasons, anything from 13 weeks down to as little as six;

- Rapid trend changes, particularly in womenswear;

- and (and this could be important in today’s economic conditions) the need for tight control over inventory levels and mark-downs.

Speed to market is all about lead times. But lead times are composed of a number of factors:

- The duration of the design and development process;

- The availability of ex-stock fabric, or the need to weave specifically for that purchase order on that garment;

- The manufacturing lead time, which is itself composed of planning patterns and markers, cutting, loading onto the sewing line, sewing, finishing, pressing and bagging;

- Shipping;

- Processing at a brand or retailer’s warehouse;

- Distributing to branded customers or the retailer’s stores.

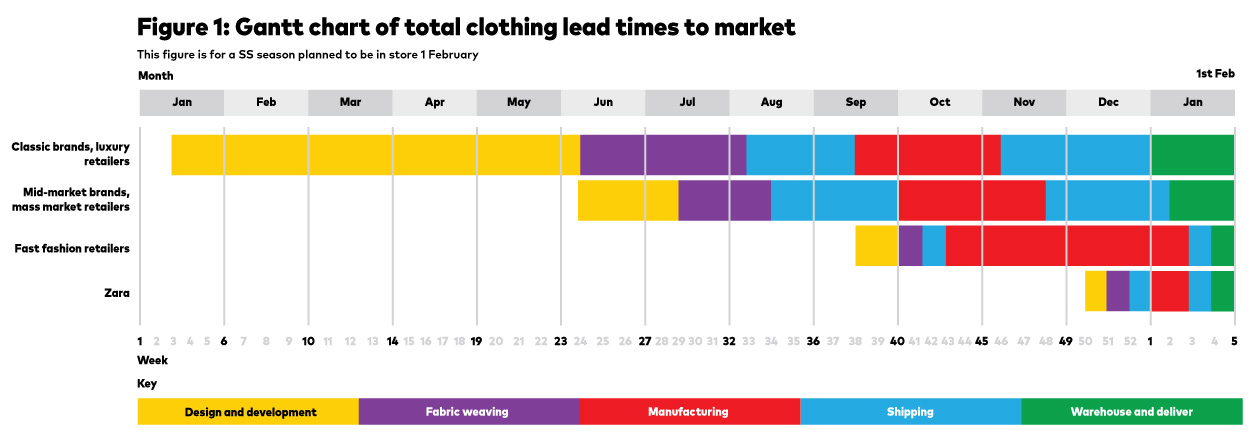

Classic brands and luxury retailers used to take a year to do this. Mid-market brands and mass own-label retailers using low-cost countries typically required six to eight months. Fast fashion got this down to 16-18 weeks, so that they could copy designer merchandise. And Zara now says it can do the whole process in eight weeks. This is shown as a Gantt chart in Figure 1:

Now, some things are immutable. If shipping is by boat from the Far East to the UK, it will take six weeks. If the fabric is unique, being woven in Europe and shipped by sea to the Far East for garment manufacture, it will take six weeks. But we can:

- Compress design and development time;

- Use ex-stock, not unique bespoke fabric;

- Reduce shipping time by being either domestic or near shore;

- Compress our warehouse and distribution activities.

Effectively, what I am saying is that the fashion industry was indulgent and slow. It is not any more. But to arrive at Zara’s eight weeks requires instant and brave decision making. My two US and UK domestic manufacturing example companies rely on this from their customers. How it affects the way they operate is covered in the next section.

Domestic manufacturing can offer the shortest lead times possible. The two example domestic manufacturers interview remarks (Section 7) suggest a normal time of 3-4 weeks and on occasion as little as two weeks.

Other non-cost factors

Cost and time are the two big factors influencing the low-cost versus domestic manufacturing decision. There are however, non-cost factors, some of which are quite emotional. They include:

- Ethical sourcing

- Sustainable sourcing

- Fair trade

- Transparency in the supply chain

- Nationalism

- Protectionism

The interviews in Section 7 elaborate on these factors.

The exit margin argument

To begin with, I am going to ignore the non-cost subjective and potentially emotional factors. I am going to investigate the argument that using domestic manufacturing is good for the buying customer, because it allows in-season short lead time orders to react to how well the garment is selling.

I will assume that:

- The domestic orders are small;

- Fabric is available ex-stock;

- The manufacturing and delivery lead time is 3 weeks.

The garment is the one explained in Table 1 quoted at

- £10.35 from the low-cost supplier;

- £15.26 from the domestic supplier;

- A cost premium for domestic of 47%.

There are three scenarios:

- 1: Buy on a seasonal sales forecast from low-cost. If it fails to meet that forecast by week 5 of 10, measured as a sell-through %, do a markdown that manages to clear the stock by the end of the season.

- 2: Buy 70% of the forecast from the low-cost supplier. If it fails to meet that forecast by week 5 of 10, measured as a sell-through %, buy a reduced quantity domestically that sells out before the end of week 10.

- 3: Buy entirely domestically, but in three separate orders, an initial order followed by a second and third order based on actual sell-through performance. Again, the garment sells out before the end of week 10.

Table 2 gives the results from the three approaches above. These are summary figures taken from the detailed calculations that can be obtained from Malcolm Newbery Consulting.

Table 2: Margins achieved from low cost, partial re-shoring, total domestic

Mathematically, the best solution is partial re-shoring. The retail buyer:

- Sells 950 units, for £23,750 exc VAT, makes £12,690 gross margin (53.4%) and incurs no markdown loss.

Buying low cost he:

- Sells 1,000 units for £20,000 exc VAT, makes £9.650 gross margin (48.3%) and incurs markdown loss of £5,000.

Buying totally domestic he:

- Sells 900 units, for £22,500 exc VAT, makes £8,613 gross margin (38.3%) and incurs no markdown loss.

So, why doesn’t everybody do partial re-shoring? Because:

- It requires more sophisticated merchandise planning by the retailer.

- It needs complex in season sell-through computer reports.

- It forces very fast decision-making by the buyer/merchandiser team.

- It needs complicated fabric purchasing controls.

- But above all, it depends on a very quick and flexible domestic manufacturing partner.

To make this theoretical argument for the advantages of re-shoring practical, just-style has interviewed two companies, one in the US and one in the UK. The companies are Suuchi Inc based in New Jersey, New York State; and Fashion-Enter based in London, England. Neither would traditionally be thought of as capable of surviving and prospering in a low-cost sourcing world.

We asked them six specific sourcing questions to which we got the following answers:

Q1: What, in general terms and as a %, do you think the difference in landed price is between you (US and UK) and China?

A1: Suuchi – “The % varies from project to project, at times we can be 30% more expensive than China, all the way to 50%. The biggest differentiator is that the MOQ’s are much lower stateside, which allows brands to stay lean and reduces the needed investment per production run. Although the initial investment might be higher, brands save thousands of dollars avoiding customs fees, lost inventory, low-quality products, and delays in receiving their final products.”

A1: Fashion-Enter – “We cannot answer that question, because we do not have data for China costs. But we know that we are more competitive on low work content garments.”

These answers corroborate both the cost figures in Table 1, and the views put forward in a just-style article about the competitiveness of high and low-cost manufacturing on different garment types.

Q2: What is your average lead time from customer order to delivery, assuming that the fabric is available immediately?

A2: Suuchi – “Once all fabrics and trims are in-house, we say to estimate for 4-6 weeks for product development and another 4-6 weeks for a finished product.”

A2: Fashion-Enter – “After product development time, we can manufacture in 3-4 weeks, and sometimes in 2. Of course this depends entirely on the retailer working very closely with us. It also depends on our arrangements with UK fabric suppliers, which are very flexible and quick. It is all about being nimble.”

Fashion-Enter also quoted a specific example of speed and flexibility. “We had an order for pink bulk dresses. We quoted 6 weeks (3 weeks fabric production/sealer and 3 garment manufacture). Fabric came in 3 weeks. We sent bulk to customer for approval. Bulk was fine but this shade had stopped selling so they requested we swap to black (stock) and use the pink fabric on skirts (which are still selling). We did this and delivered the garments within 3 weeks. Had the garments been bought from Asia, at 3 weeks before the delivery was due the garments would be on the sea, therefore changes could not be made. Therefore discount would probably have had to be applied immediately to facilitate timely sell-through, whereas the UK made garment will probably sell through at full price.”

Q3: What customers value your domestic manufacturing and therefore buy from you on a regular basis?

A3: Neither company was prepared to quote specific customer names, for client confidentiality reasons. But we do know that they both have a substantial customer list of high profile retailers.

Q4: What other non-cost factors (such as quality, reliability, the “made in” label, etc) help you sell?

A4: Suuchi – “Transparency within our supply chain through the use of our PLM platform is a big selling point for our clients (see more about PLM in Question 5). Being in a similar time zone, speaking the same language, and quick response times have been valuable attributes to our clients. Then the quality, reliability, and “Made in USA” label are important as well. A lot of our clients come to us after having bad experiences with overseas production. Being woman-owned is also something that has helped differentiate us from the competition, while providing our clients with branding power.”

A4: Fashion-Enter – “Our quality is highly regarded. Our reliability is excellent because of our nimbleness. And, of course, there is a “Made in UK” advantage. But we rely on facts to persuade potential customers to use us, not on emotion. The facts are based on speed-to-market and the exit margin the customer achieves by sourcing in the UK.”

Q5: Do your PLM (product lifecycle management) systems give you any advantages over low cost suppliers?

A5: Suuchi –”Our PLM, the Suuchi Grid, provides our clients with a fully visible supply chain, which eliminates any guesswork on when your production is going to be completed. This allows our clients to strategically plan around each stage to ensure they have successful product launches. Our PLM is also a communication hub for clients, manufacturers and suppliers, which eliminates missed emails and speeds up response times. Product-related documents are stored on the Suuchi Cloud, which helps brands keep everything in one secure location. With the recent launch of our PLM app, clients are now able to track their projects on-the-go. All of these features provide Suuchi Inc with a major advantage over traditional apparel manufacturers.”

A5: Fashion-Enter – “They undoubtedly do. We have integrated PLM incorporating CAD and CAM for design and product development, cutting and work-in-progress control. Without this, we could not be nimble. We are happy to share this data transparently with our customers, if they want it.”

Q6: What do you think the potential is for domestic manufacturing in terms of:

– Your growth?

– The domestic industry growth as a % of the market?

A6: Suuchi – “With a 30% month-to-month growth rate, we have seen first-hand the potential for hyper-growth and we’re just getting started! As our process continues to evolve through automation and the Suuchi Grid, we are confident that Suuchi Inc will become the leading US-based apparel manufacturer in the coming years.”

A6: Fashion-Enter – “We are currently investing in enlarging our production capacity, with an extension to our factory which will open in April 2019. But the problem of manufacturing growth in London is getting the sewing machinists. The problem is the churn of sewers who cannot work to our levels of speed, accuracy and efficiency. It is not a constraint. It just makes growth slower. Training stitchers is always a priority for us.”

Conclusion

There does appear to be a strong case for domestic or near-shoring of part of a retailer’s buy. It is based on:

- The achieved exit margin, which is itself dependent on

- The avoidance of mark-downs;

- The achievement of 100% sell-through.

These themselves depend on:

- The availability of short lead-time fabric;

- Nimble and flexible manufacturing;

- Sophisticated CAD and CAM to manage a transparent supply chain.

My two example companies are proving that this can be done, although the jury is still out on whether this will lead to a significant rise in manufacturing in the US and UK. That said, the prospects appear bright for my two example companies. How many others either domestic or near-shore will follow suit?