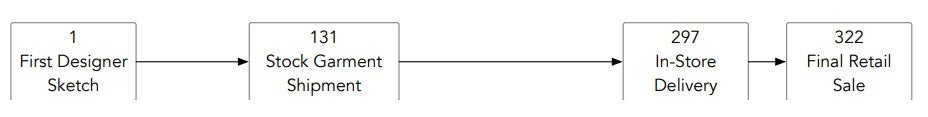

The digitised apparel supply chain defines the steps in the apparel process. The process begins with the product-design concept: Step 1: First Designer Sketch, and can end at various predetermined steps such as production completed, in-store delivery, or even to the point when the final stock garment is sold.

I am sure the actual supply chain does indeed exist somewhere out in the ether. We cannot see it. We cannot even imagine it. What we have is our best effort to create a picture of the steps in the process, which in itself is neither complete nor accurate and therefore of very little practical use.

Our current supply-chain picture is linear, limited to a series of distinct and separate steps, where all movement is unidirectional — step 1 followed by step 2 which in turn is followed by step 3 all the way up to some predetermined end, where step 321 is followed by step 322.

What are the problems when working with a digitised apparel supply chain

The first problem is that reality is not clear cut and indeed can be quite messy. Every day, operational professionals must deal in a dynamic world where very little is fixed, and much is by nature unforeseen. For example:

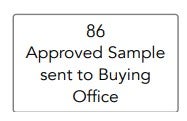

The sample has been approved but, more often than not this leads to a series of problems, none of which appear in the supply chain such as:

The Free On Board (FOB) Price is outside the target

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataThe selected factory cannot make the garment

At this point, we would expect the work to return to the product-development phase, for necessary redesign to eliminate the problems.

However, under the supply chain regime, this is no longer possible. Management expects two solutions, neither of which makes sense.

Go to a cheaper factory

Go to a better factory

The result is that a merchandiser working in a branch office in Chittagong will all too often work with the local factory to change the design thus removing both the cost and quality assurance problems. Management is pleased the buying office has once again operated within the confines of the supply chain but fails to recognise that 20 weeks of the product development process is now out the window.

This is but the first problem. The second and far greater problem occurs when we try to digitise the supply chain, by calculating precise times and costs.

Think of a supply chain as a detailed picture. Imagine a still-life painting of vegetables hanging on the wall, where each piece is exact —The celery, carrots, lettuce, etc. are each painted so realistically that you would think they are real. Now imagine taking the painting off the wall and chopping it up into little pieces to make a salad.

Pictures are not real. Reality is real. To put it another way pictures are static and reality is dynamic.

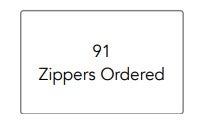

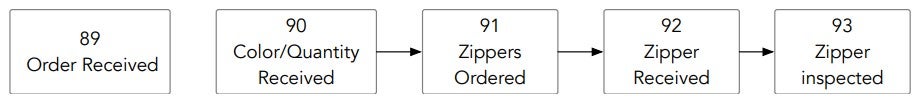

Take the simplest step in the supply chain: Buying Zippers. This might be a single step such as:

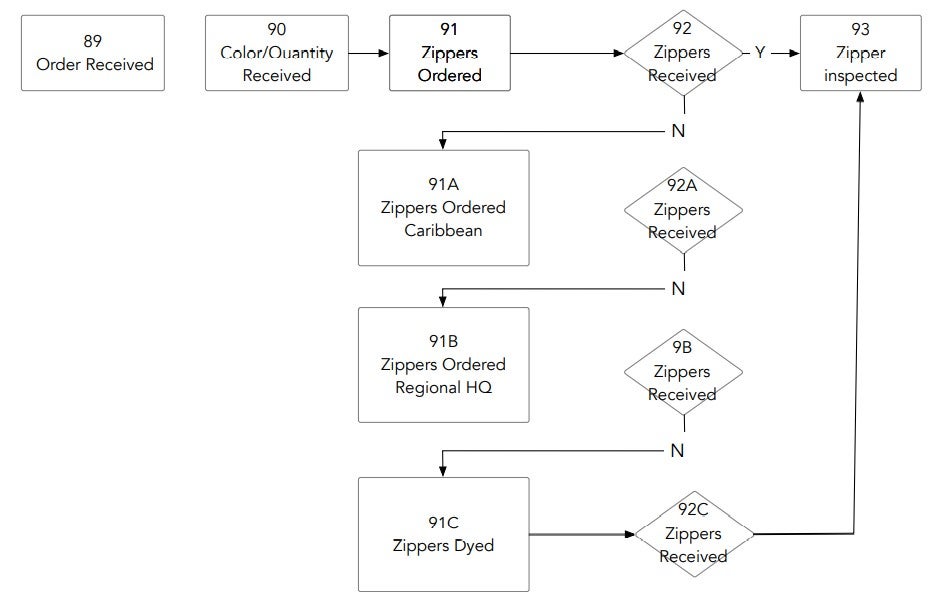

Or broken-down into a series of steps:

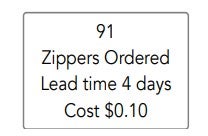

When digitised we have specific data:

Lead Time: Based on past experience, YKK the designated zipper supplier would take 3-4 days maximum.

Cost: Factory purchase order, YKK invoice, Factory payment record and the price is set in stone as it must be US$0.10 per piece (or $10.00 per piece).

99.9% of the time reality and the supply chain coincide. The problem is with the 0.1%. This is where reality diverges from the picture.

For example:

200 machine factory located in El Salvador

Step 89: Receives order: FOB price and delivery date agreed.

Step 90: Requires zippers in four colours

The process begins:

Day 3: Only three colours received and colour blue 497 is not in stock.

This isn’t a problem as you can check with YKK branches in Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua

Day 6: Blue 497 is unavailable in the Caribbean area

This isn’t a problem as you can check with YKK Regional Headquarters Mexico

Day 9: Blue 497 is unavailable so must be dyed

Dyeing Time is 21 days + 3 days transport

Day 33: Blue 497 arrives at factory

To understand the severity of the problem, we must return to step 89. The 200 machine factory has guaranteed delivery and is now 30 days late. The factory contacts the customer’s global buying office in Hong Kong who in turn contacts head office in New York.

At this point the parent company is faced with two equally bad options:

- They can accept 30 days late shipment, which will result in increased markdowns.

- They can cancel, which will result in consequential losses, plus losses arising from the cost of the unused fabric.

More importantly, neither option will prevent future problems because neither option deals with the cause: Zipper cost. Indeed, because of the nature of the digitised supply chain, the price of the zipper must remain at $0.10 per piece, when in fact the cost of that same zipper now exceeds $10.00 per piece.

The good news is this disaster will only occur once in one-thousand orders. The bad news is that the problem is not limited to just the zipper. It carries over to all trim (sub-materials + packing) products. Every garment requires trim, as few as 5 (basic T-shirts) to as many as 25 (lined overcoats).

What started as a problem involving a single trim item has now increased 5-25 fold.

What is the solution when working with a digitised apparel supply chain

As with the 24 year old merchandiser in Chittagong, in practice the buying does have a solution:

Go back to the beginning. The problem is neither markdowns nor consequential loss. It is the zipper: Specifically blue 497.

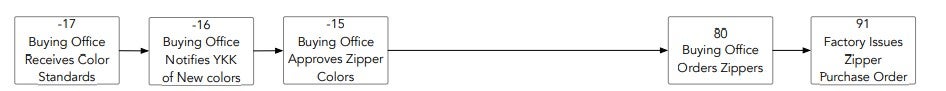

We must ask ourselves, when was the buying office first notified that going forward, blue 497 would be a colour?

In almost all companies the selection of colours is made long before the beginning of the garment design process.

Since the supply chain begins with the garment design, the buying office will almost invariably receive colour standards prior to step 1 in the supply chain.

Once we abandon the picture and move to reality, the solution is relatively simple:

Zipper colour approvals take place between YKK and the Customer’s global buying

office long before garment design takes place. The global buying office orders the zippers before the factory has been selected, leaving the factory selected to produce the order to issue a purchase order. The best news is that well managed buying offices sensibly do not rely on the supply chain for their decision making process.

How to escape from the digitised apparel supply chain trap

The apparel supply chain has two fundamental flaws. The first is almost universally recognised: The “steps” in the supply chain are not fixed, discrete or separate as they are based on interrelated variable factories. Changes in

any one step will affect other steps, which in turn changes yet more steps until every link in entire process is constantly in a state of flux. As any working professional can tell you, the job of everyone in the buying office and at the supplying factory is crisis-management. Rather than a simple linear chain, it is a complex multidimensional process.

What was once defined as a single step…

…Is now a far more complex series, virtually none of which appears in the supply chain:

The second is of primary concern but regrettably still not understood: Price does not equal cost. In fact, the two are totally unrelated. The need to conflate cost with price distorts the entire decision making process.

As we can see from the zipper example, the price of the zipper was $0.10 per piece, which is undeniably true. However, as in the example above, the cost was $10.00 per piece, which is also undeniably true. Because of our misconception that price = cost, we spend our time trying to reduce the price as listed in the digitised supply

chain from $0.10 to $0.08 without even recognising the real problem — which does not appear anywhere in the supply chain —the $10.00 cost, which is 100 times more important.

We are caught up in a problem that has plagued the apparel industry for generations. Our decision-making process is flawed. We concentrate our time, efforts and capital, in an effort to save pennies rather than dollars.

The strategy to digitise the supply chain is simply the latest in a long line of flawed concepts.